(RxWiki News) Calcium’s role in reducing cancer risks is controversial. In some studies, the mineral was shown to reduce the risks of abnormal colorectal growths that can lead to cancer.

Other studies didn’t find that link. A new study may solve the conundrum.

High calcium intake appears to benefit people who have alterations in one or two genes. These genes are involved in how calcium is absorbed.

People with changes in both genes who consumed high amounts calcium had a 69 percent lower risk of developing colorectal adenomas, which are abnormal growths that can become cancerous.

"Talk to your pharmacist about supplements."

Xiangzhu Zhu, MD, MPH, staff scientist in the Division of Epidemiology in the Department of Medicine at Vanderbilt-Ingram Cancer Center and Vanderbilt University School of Medicine in Nashville, Tenn., led the two-phase study.

The scientists wanted to explore whether changes in 14 genes that control calcium and magnesium levels affected colorectal adenoma risk. They also wanted to see what, if any, connections there were between the genetic changes, calcium/magnesium intake and adenoma risk.

To test the various connections, the researchers examined data on 1,800 people who had colorectal abnormalities and nearly 4,000 healthy controls.

Researchers found that there were two key genes involved - KCNJ1 and SLC12A1, both of which control how the body reabsorbs calcium in the kidney.

Here’s what the researchers learned:

- 13 percent of participants had changes in both genes.

- These genetic alterations significantly increased risk of colorectal adenoma in people who consumed very little calcium.

- Highest calcium intake reduced adenoma risks by 39 percent in patients with one altered gene.

- People with changes in both genes who consumed high amounts of calcium had a 69 percent lower adenoma risk.

- High calcium intake was also associated with an 89 percent reduced risks for advanced or multiple adenomas in people who had mutations in both genes.

- Calcium intake did not affect adenoma risks in people without changes in one or both the genes.

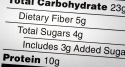

Dr. Zhu said that patients who have changes in the genes need to increase their calcium intake to over 1,000 mg per day.

“Our results may provide one possible explanation for the inconsistency in previous studies on calcium intake and colorectal abnormalities because calcium may primarily prevent colorectal cancer in the early stage and reduce risk only among those with genetic changes in calcium reabsorption, which involves KCNJ1 and SLC12A1,” Dr. Zhu said.

"This study led by Dr. Zhu and colleagues showed that a protective effect of calcium intake on colorectal cancer may depend on genes involved in calcium reabsorption in the kidney," one of the study's co-authors, Edward Giovannucci, MD, ScD, professor of nutrition and epidemiology at the Harvard School of Public Health, told dailyRx News. "If confirmed, this finding can help identify individuals who may require higher calcium intake to prevent colorectal cancer because of a genetic predisposition."

Results from this research were presented at the American Association for Cancer Research (AACR) Annual Meeting 2013. The study was funded by National Institutes of Health (National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine/Office of Dietary Supplements).

All research is considered preliminary before it is published in a peer-reviewed journal.